ECMO for ARDS; car crash RCT

Here is the supplementary material

This one had a fair bit of attention on Twitter from the likes of Frank Harrell (here) and Andrew Althouse (here) so I thought it was worth posting something.

A new trial in the New England Journal tested ECMO (extracorporeal membrane oxygenation) for patients with severe ARDS (acute respiratory distress syndrome). It used a group sequential type design that allowed early stopping either for evidence of effectiveness and for futility. In fact the trial stopped early, for futility, after the fourth interim analysis, when 240 out of the planned maximum of 331 patients had been recruited.

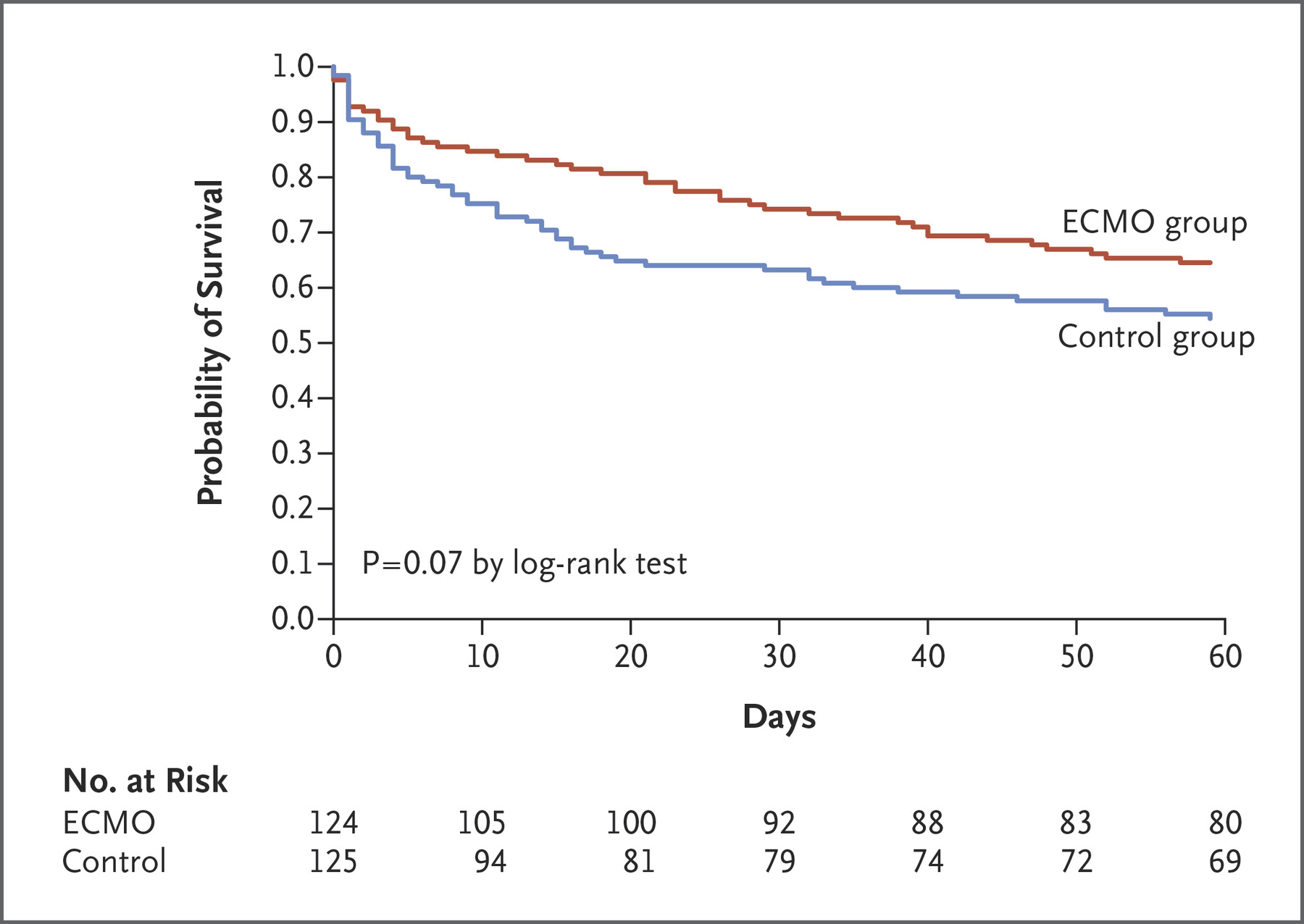

The results for 60 day mortality was that 44 /124 patients (35%) in the ECMO group died and 57/125 (46%) in the control group (risk ratio 0.76; 95% confidence interval, 0.55 to 1.04; P=0.09. The survival plot looked like this:

And the conclusion (from the abstract) said:

Among patients with very severe ARDS, 60-day mortality was not significantly lower with ECMO than with a strategy of conventional mechanical ventilation…

The accompanying NEJM editorial said:

Nevertheless, at least one important conclusion can be drawn — the routine use of ECMO in patients with severe ARDS is not superior to the use of ECMO as a rescue maneuver in patients whose condition has deteriorated further.

Both fairly surprising statements, given the results, as is the fact that the trial stopped for futility, even though ECMO was looking substantially better than control. There are so many issues with this trial it’s hard to know where to start, but here are a few things that stood out to me:

- Interpretation. Here is a prime example of the way significance testing encourages a naive binary approach to results - “it works or it doesn’t work”. Yes, the result did not reach the “statistical significance” threshold. But it’s looking pretty promising! In any case it’s completely wrong to interpret non-significance as evidence of no effect; the old “absence of evidence is not evidence of absence” thing.

- Planning. The trial sample size (331) was based on getting “significance” (p<0.05) with a probability of 0.8, if the true difference was a reduction in 60-day mortality from 60% in the control group to 40% in the ECMO group. Think about what that means. Even if the difference is HUGE (it’s a risk ratio of 0.67, and effects that size in any field are incredibly rare), we’re only going to get p<0.05 four times out of five if we do loads of replicates of the trial. So there’s a substantial chance (20%) that even with such a massive true effect, the result is going to be non-significant. When you take into account that much smaller effects would also be clinically important, and the incidence of the outcome was lower in the trial than anticipated, non-significance in the presence of clinically important true effects is even more likely. You might expect the interpretation to take such issues into account but instead we just get mechanical application of p > 0.05.

- Early stopping. The futility stopping rule was based on a low probability of achieving significance. That’s a problem - because, overall, the trial had a low probability of getting p < 0.05, so it’s likely that a lot of possible results could end up satisfying the futility stopping rule. That’s what in fact happened, Data that suggested benefit triggered the futility rule - because the trial was designed around such a huge benefit, more realistic levels of benefit were unlikely to result in “statistical significance.” So that’s a failure in trial design and planning really; a failure to think through the consequences of the decisions that were taken and what might plausibly happen when the trial was conducted. A better plan would have been to require evidence of no useful treatment effect in order to stop for futility, not simply unlikeliness to achieve a massive difference. So something like a low probability that mortality with ECMO is more than 2% better would give a sensible reason to stop early. The supplemetary material contains an analysis of what might have happened if they had continued to the next interim analysis. This suggests 100% probability of stopping then, about 90% for futility, but 10% for efficacy. So the trial’s stopping rule managed to stop a trial that had a 10% chance of satisfying the extremely strict efficacy criterion at the next interim analysis. That seems pretty remarkable to me.

I could go on and on about this but I’ll keep it short for the moment. May add more later if I find time and motivation.